work in progress

Modes of Dink: a pickleball fiction

Boomer McWillie had never been much of an athlete. Growing up, he had been one of those kids who were often unchosen when a group split into two teams for softball. He liked sports, watched professional baseball and knew how to draw all the emblems that went on the teams’ caps. He was good at that kind of stuff.

For many decades, like quite a few of us, he had mistreated his given body – gracile mesomorph – by subjecting it to intermittent wine and/or reefer use. He had pummeled the body into bad posture, and aside from much walking when he owned no car, no exercise at all from years 17-40. By his mid-sixties — predictably enough — he had begun to develop the usual health problems of his demographic.

One sudden day, walking (without a shirt) to get his mail, he heard a kid two houses down the block (there were a couple of them wandering around an above-ground pool): “Hah! There goes a man!” He went back inside and then thought Hey! They meant me! They were being derisive, those kids! It was not a good feeling.

One night he saw a girl wearing a t-shirt that read “I Dink Therefore I Am.” When he asked what it meant, and she told him, he became forthwith, as they say, a convert to the religious sport of Pickleball.

“Ah, screw this grief counselling shit.”

McWillie couldn’t help but overhear the guy in the back talking on what appeared to be an old-fashioned flip phone. Off and on, mostly on, he’d been attending the Garalusa Grief Group (led by Larry, local poetry professor) for several months, really for no reason aside from the joy it gave him to hear women’s voices.

He rarely spoke and was rarely given a reason to do so, sitting on the edge of the chair-crescent in a state of benevolent receptivity, quiet but not scarily so, secretly slightly high from a little gummy he’d had after breakfast.

“Whatta ya say, man?” he asked the guy on the phone.

Putting his hand over the phone, he looked at McWillie, widened his eyes, and said, “Fuck this grief counselling shit. Let’s go get a beer.”

There was a bar several streets down from the old church. Nice cool night. “Alright, let’s go.” Nobody would miss him. He’d apologize next time he attended.

The guy introduced himself as Sammy. “Mine is court-mandated, you know, so I have to attend at least x number of meetings. I had the choice of grief or trauma, I chose grief.”

“Uh, or — what?”

“Lose my clown license.”

McWillie frowned. “Oh. You’re a professional clown, then?”

“You’re gullible, aren’t you? I like that in a person. What do you do for fun, dude?” He eyed McWillie sympathetically.

“Pickleball, actually.”

“Aw, naw. Me too.”

“How long? I been at it a few months.”

“About the same here.”

“You want head to Gray Rock and play a few games?”

“Singles? These legs ain’t built for single matches.”

“Hah! There’ll be somebody there. But let’s have those beers first.”

“Well Sam,” McWillie asks, “what happened to your wife?”

“I keep saying I lost my wife because I really think Xenia will turn up again someday, though she — “

“What? So she didn’t die? I thought you — “

“No, like I said, I lost her. She had sundog syndrome or whatever it’s called. Dementia was there but we joked about it, mostly. I have a bit of it myself.”

“I hadn’t, uh — go on.”

“I guess it will be two years this-coming December, she just wandered off and was not immediately found, so — so we don’t exactly know what to think about her. People were coming to the house to celebrate Thanksgiving — boy were they shocked. I just can’t see her or feel her as deceased, though the cops tell me that after this long, well, there’s not much hope aside from faint glimmers.” He looked at McWillie. “So what about you?”

Boomer, whose real name was Lawrence though he never told anyone, told his new friend the story of how his next-to-last wife had gotten tired of him, amicably divorced him, and was now living more or less happily in Seattle with her children.

“Not my kids,” he said, “though I was their dad for awhile. None of us talk much or visit, ever. I’m kind of stuck in this solitude that I had better like since it don’t seem like I’m about to escape it any time soon, right?”

“Uh, right, yeah I guess. Want to go try to find a game or two?”

Silence walking back to the Grief & Trauma Center, shoes crunching broken tree-limbs (storms late last night) on the ancient sidewalks.

“Sometimes I think I see Xenia,” Sammy blurted out.

“Damn.”

“Yeah. I don’t go up to the people or anything, though, you know.”

“Right. I wouldn’t either. It must be tough, this not-knowing about your wife….”

“Getting used to it to some degree. Losing one’s self in mindless pleasures helps, too, right? Am I right, Boomer? Is that really your name?”

“Pretty much.”

“You know I went and camped out pretty much in the woods behind our house after Xenia got lost. I had the skills and the gear, nothing else to do, and there was the chance that I might find her. Very pretty, mild days. I didn’t hunt. I stopped hunting years ago. I forgot about football.”

“Damn.”

“Yeah, shit. Sorry to whine so much.”

“Nah, man, it’s okay, it ain’t — “

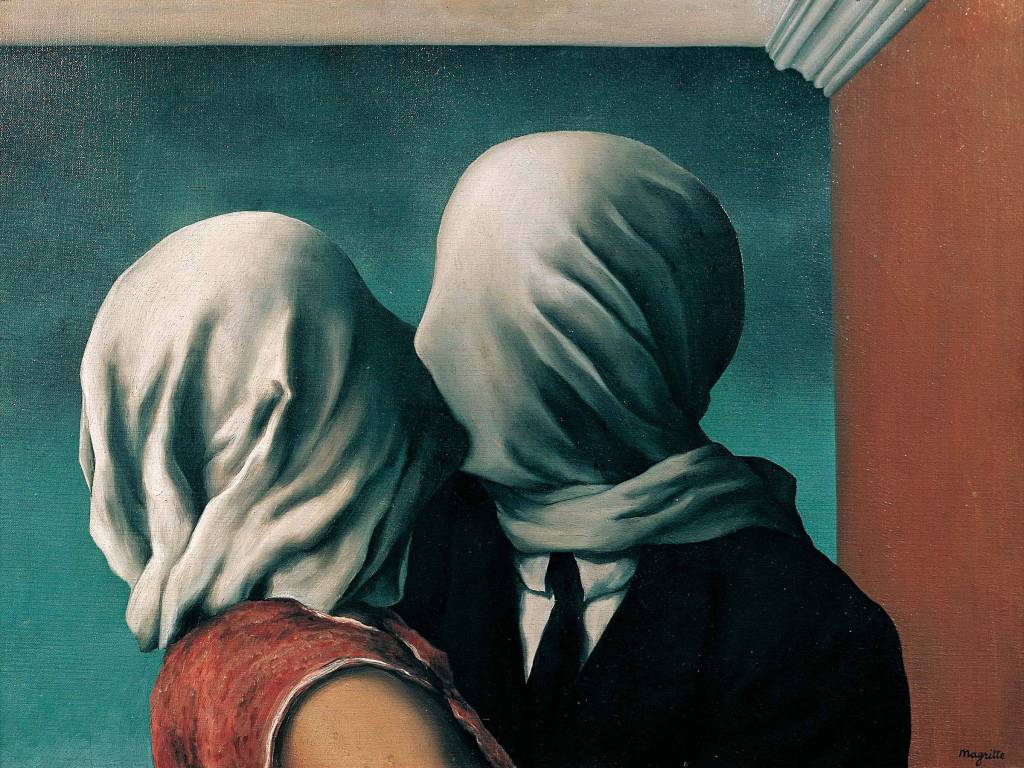

Sammy stopped and reached into his wallet, pulled out an ancient tiny photograph of a dark-haired woman looking toward the photographer’s left shoulder. “There she is.”

McWillie grinned at his friend, knowing he was being put on. “That can’t be her.”

“Why?”

“Because that’s the woman on the cover of a book I once read, and it can’t possibly be your ex-wife.”

“We’re still married.”

“Okay, sorry, but still, that photo comes from Richard Brautigan’sThe Revenge of the Lawn.“

“I don’t know who you are talking about.”

Xenia had been acting pretty odd, and she was ten years older than he in their 30-year marriage, but Sammy truly had no idea what was about to happen to him when she vanished. He took her far too much for granted.

It was a simple sort of day, an unaffected clear autumn day (like 9/11/01, came the later thought); they were planning a short late-afternoon trip to visit grand-children, but when he returned from work (he then had a part-time job running the morning desk of a space-rental agency), she was not in the house.

A cup of lukewarm hyacinth tea sat on the table, not a drop spilled. She had closed the door behind her. Purse gone, phone still in the drawer where it had been for a few months, since her cognitive problems had begun.

If authorities thought she had been abducted, they were not sharing this information with Sammy.

“This happens a lot, you know,” said the policeman.

“Really? How — ?”

“You see those grey alerts, that’s who it is, mostly.”

” ‘Grey alert?’ “

With little patience, the cop explained the phenomena: folks got “the dementia,” wandered away from their homes near sundown, either got killed or died later on. Sammy swore the guy used the phrase not too distant future.

Sammy asked, “Do they just come back home, ever?”

“Sometimes.” Sammy saw them after being told what they were: bulletins that gave the name and address of the vanished elder, perhaps a photo, along with careful words about “mental states.”

You just don’t expect your spouse to so suddenly vanish. If she’d planned a visit, or was away on a lengthy hospital stay (as had happened), that’s different of course. Sammy’s mind could not get purchase on it. It was like trying to run in deep fine sand, or more like really trying to see a star at night — the more you dwelt on seeing it, the more it got away from you. Right after this phase, he began sleeping in a tent in various outdoor locales not far from his home, as he told Boomer.

Dozens of rather excruciating weeks later, he found that she was, indeed, still listed on the missing persons list for the county. He had been stunned into inertia, shut down, stopped working, stayed at home waiting for her to meander back. He was sure that is what would happen; even had a little “Now Xenia” message all ready for the moment of relief. Didn’t happen, day after day. He sat near the front windows and kept his grey eyes peeled on passers-by. He had stopped drinking at the time but bought a bottle of whiskey on St. Patrick’s Day, “for visitors.” Weeks seemed to pass at the speed of months. Was it along this time he had started playing this silly game of pickleball? He could not remember, try as he did, linking things up temporally in his worn brain, hoping connections might spark across the gray matter, but nah, not today. He sipped a little whiskey but that did not help much.

Eventually Sammy would shuck his gloomy thoughts and head over to the Moby Dink, biggest private pickleball club in town, for some practice.

“Allright. I see three choices.”

“I see more but go ahead.”

“We play the tournament nude. One. We play semi-clothed: two. We play dressed normally, three, my favorite and the option getting my vote.”

They were sitting at a railroad crossing in Bonifay, Florida. On a street named Waukesha, just behind them and one mistaken GPS-turn away, sat the Fairy Tails Pet Groomery and next to it, tucked back, a taut door that led into the Jagged Edge Hair Design Studio.

What life must be like down here, eh? Neither had to ask the other this question; the environment itself seemed to make a similar query. Flat, unimpressive, sandy.

“There’s always the unexpected, right, the thing that nobody thought would happen.”

“Deus ex machina.”

“Uh huh.” Testudines almost missed the turn for I-10 but at the last minute managed to whip the Hyundai sharply up an interstate ramp. “Almost there.”

At a diner on the beach, they ran into a waitress who was involved in the pickleball/tennis disturbances in Lanark Village. “Cops were called. People whackin’ each other with rackets and paddles. Loud.” Her name was not Mona, though her namecard said that. She advised them thus: “Avoid the zealots.”

“Florida is pretty weird, don’t you think? What happened to Florida?”

“Ah. Don’t judge a people by the people they elect to govern.”

“Why not,” fumed McWillie, “isn’t it as good a method of judging as any?”

Testudines hit his vape pen, stared out into the warm air beyond his window.

“I’m not one to go displaying my body in front of anybody around here,” he averred.

“Yeah, I hear you. Only people with nice bodies should display them — otherwise, it’s a visual abomination.”

“But do we want to be like the only clothed people at an orgy?”

“It’s a pickleball tournament, mac, not an orgy. You’re overcomplicating it, which I see is a — “

“Not yet anyway.” Meditatively, he said, “I have been struck in tender places — you might even say it was a ‘ball-on-balls’ incident.”

“Oh now that’s clever!”

“It hurt, man, is the point! Nekkid is not the way to go with this sport, especially since we are apt to get up near the kitchen line like you’re supposed to, and we’ll get hurt. Match over. You all curled up in the fetal position on the court, hollerin’.” He almost smiled.

Boomer’s mind ranged to that jock world of which he had never been a part. A locker-room world.

“You know, Tex Watson was a winning quarterback in east Texas in his youth.”

“Whozat?”

“The Manson acolyte.”

They lost all their matches, natch, with the wind crossing them and pulling Boomer’s spins the wrong way. His partner drank too many Red Bulls between matches, but that was a small thing. Their changing sets of opponents seemed to know how to handle anything thrown at them and graciously handed their asses to them in game after game: 11-5, 11-2, 11-5, 11-3. Almost no one played naked.

They drove north the following morning, and no one suggesting tournaments further east along the panhandle. Not much was said.

“I see floaters,” Testudines said near the end of the trip.

Boomer got checked into his room, found it, collapsed with an aching spine on the oversoft mattress. Check for bedbugs with the little light? Nah, too tired. It’s a long drive to Illinois, close to five hours and he’d stopped only three or four times, mostly to pee.

Now he got his phone fixed up on speaker and called his brother Bill. It was a great view of some historic part of the Ohio river, and he was viewing it from the very edge of Illinois, though the bank across the way was Kentucky and he had a lot to talk about with his elder sibling, who lived a few states away but always took time out of his managerial duties at some sort of office complex to call Boomer back.

“Little brother, how you doing?”

Boomer slumped back into his bed. “I’m enroute to a tournament. Practically there.”

“Still doing the pickleball thang, yeah?”

“Yeah. I’m at a Holiday Inn Express just off Interstate 24 — if you need to search for the body — as we used to say to Mom — “

“I can’t wait to retire.”

“Well why don’t you?”

“Agh,” Bill seemed to spit at the very thought. “Not yet.”

Boomer had heard this from so many people. They worked and worked and worked at their hated yet inescapably secure jobs, delaying retirement, building up a bigger nest egg. By the time they stopped working, death was upon them.

As they were chatting, the high-potency Δ9 Kitkat started to make itself felt and Boomer forgot why he had called his brother. He managed to swing the conversation back around to a normal place and got off the phone but by then had forgotten everything they’d said to one another. Oh well. He put on his headphones, set to an Audible book about Watergate, and went for a walk along the river, thinking few thoughts, sweating into his slinky sport shirt, loping cluelessly along. The book’s words scarcely registered.

Why was he doing this? How many more years did he have left to scrimble around the world like this? Wasn’t death, or at least painful disease, right around the next temporal corner?

Why was he thinking about death so much? He should be pondering pickleball strategy, but since his main partner was out recovering from a retinal detachment, the lazy slug, he’d have to take whatever lonesome stranger they put him with. I’m a geezer, he mentally sighed. That’s why mortality seems so close, as close as that giant tugboat or whatever the fuck it was out there on the Ohio . . .

Boomer’s partner, unfortunately for their Fall tournament schedule, put himself on the DL — retinal detachment surgery. Common as shin splints among the elderly, it is said.

“How’d you get it?” Boomer asked him on the phone, having been given the news by text.

“They don’t know. Inherited. Blows to the head.”

“Huh. Remember at that Sib-a-rite tournament in Apalachicola where you slipped on that melted fruit rollup?”

There was a little silence on the line. He could hear Sammy chewing.

“You rolled over a couple of times and then just jumped right back up, as I recall…and we won the match. But lost at that tournament.”

“We are always losing a lot. Makes you wonder why we ever played.”

“Seriously?” Boomer mulled over this twist in his partner. “I have enjoyed many losses. It was more the travel and the changes and — “

“Yeah, well, I’ll be out for a while, so I wanted to let you know.”

“‘Preciate it, dude. Let me know how you are on the recovery road. Come by anytime. Still going to the Grief place?”

“Nah.”

“You all right? You’re mighty monosyllabic for a pretty day.”

“This eye stuff is aggravating. I have to keep my head tilted an odd way. I gotta go.”

“Aight.”

“We’ll see you. Joke, the eye, get it?”

“I see, as the blind man said.”

Boomer was at a loss for a while. He couldn’t seem to find a place for himself. When he wandered to a park, ready to play, the courts always seemed full, so he’d just walk and think about adopting a dog as a cure both for his selfishness and his lonelinesss, which may have been related. But it was too hot, late that summer, for walking. It was hot everywhere, and though Boomer considered himself pretty indifferent to things like “the weather,” the weather had of late begun to capitalize itself and thus began to bother him. Like the chill in northern cities, heat kept southerners cocooned in AC inertia.

He drank more indoors, mostly beer he let go stale. He almost started smoking cigarettes again. Flipping through his online friends, he realized there would be only a few people showing up at any memorial for him, after his death. Plenty of seats for that one. He saw his namesake, Boomer Esiason, former football star, on one of the sports channels, commentating. He was aware, sitting there in his comfortable green chair, a fine La-z-boy only five years old, that his guts felt weird, tense, as if the coils of his intestines wanted to say, to growl something intelligible. Stop eating processed foods probably, or Too much cheese, dude.

Entering the venue after trotting up some big steps, Boomer realized this was, yes, why not: a pickleball church. So spacious, so austere and utilitarian, larger than many megachurches, with a sealed, peaked ceiling higher than anyone could lob and lined with thick curtained walls behind which one maneuvered — a sign spelled this out to newbies — to the many courts.

The time was right, Sunday morning. The hills in the distant, foothills merely, were a hallowed color of greenish blue. Rivers named for states were nearby.

He wouldn’t have been surprised if the minor chords of an organ had blasted out of the speakers on the big walls.

“Wel-come.” A red-bearded guy adjusted the PA. “Check. Check!!” Various tournament factotums moved around the quite enormous place, getting things ready; one lady measured net heights. A few players warmed up. A bale of t-shirts lay on a small table.

Boomer was early. He texted his partner, whom he’d never met, got a big drink of water and sat down to stretch as he had learned long ago in yoga class.

This was an athletic club in the wealthier part of this mid-south city (home once to a famous ex-Nazi German scientist), rented by the tournament folks for this three-day event. Boomer, listening to Richard Ford on his car’s sound system, had driven the eighty minutes quickly, arriving before daylight where he could find only a moribund IHOP for a sweet breakfast before searching for the address of the tournament.

A-men, he thought quietly to himself, apropos of nothing. His stomach was giggling.

He got a text back from his partner which read, “I’m on the way. Grey beard and blue shirt.”

He thought back to the shower he took that morning at 4 a.m., when a unique Boomer thought had appeared, to wit:

Maybe a mindful morning shower was all the baptism a person needed to begin a day, a life, a project, a pilgrimage.

[to be continued]

I recently [2011] attended a yoga workshop on the outer, northwestern ring of Atlanta: ten hours of yoga and talks spread out over a mid-winter weekend. We arrived on time and as my wife and I walked down the hall toward our room, I realized the teacher of this workshop was at the ice machine just behind us. “Welcome to the suburbs of Atlanta, Mr Schiffmann,” I said as he pulled up behind us. “I was at some of your workshops in Monteagle a few years back.” It was a nice way to start the weekend.

I recently [2011] attended a yoga workshop on the outer, northwestern ring of Atlanta: ten hours of yoga and talks spread out over a mid-winter weekend. We arrived on time and as my wife and I walked down the hall toward our room, I realized the teacher of this workshop was at the ice machine just behind us. “Welcome to the suburbs of Atlanta, Mr Schiffmann,” I said as he pulled up behind us. “I was at some of your workshops in Monteagle a few years back.” It was a nice way to start the weekend.